THE CHICAGO JEWISH NEWS / PAULINE DUBKIN YEARWOOD

Chicago’s urban landscape is dotted with historic former synagogues that have become churches, mostly in the African-American community.

Others have fallen victim to the wrecking ball.

But there’s only one “ballpark synagogue” in the country, and it’s flourishing within a metaphoric stone’s throw of Chicago in South Bend, Ind.

The oldest synagogue in that city now sits inside the walls of Coveleski Stadium and serves as the team store for the South Bend Silver Hawks minor league baseball team, complete with a Star of David on the roof and refurbished bimah, hardwood floors and historic chandelier on the inside.

The former Sons of Israel synagogue was once a candidate for demolition. Now, Silver Hawks fans and members of South Bend’s Jewish community agree, it isn’t going anywhere, except on the National Register of Historic Places, to which it has already been named.

The unlikely Sons of Israel story begins with a turn-of-the-20th-century Jewish neighborhood and ends (or continues) with a Jewish team owner who couldn’t bear to see the stately old building torn down.

South Bend has had a Jewish community since the 1850s, and by the early 1900s, that community was booming, according to Debra Barton Grant, former executive vice president of the Jewish Federation of St. Joseph Valley.

Grant, who is now executive vice president of the Jewish Federation of Greater Indianapolis, grew up in South Bend and says she feels a special connection to the historic old synagogue.

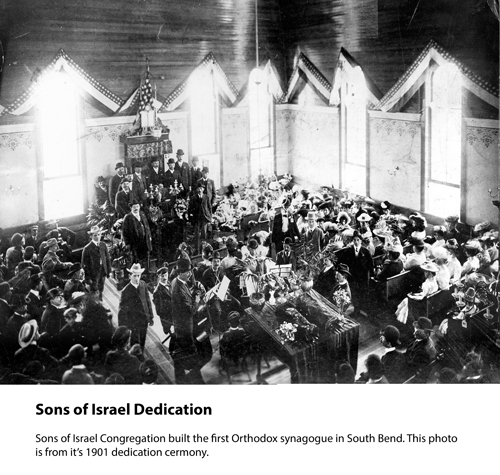

It was built in 1901 in what was then the center of a bustling immigrant neighborhood, with kosher butcher shops and bakeries, a Workmen’s Circle clubhouse and meeting hall and at least one other synagogue nearby.

It was built in the grand manner, with a round west-facing stained-glass window and an impressive chandelier on the inside.

By the middle of the last century, “there were tons of (Jewish) businesses, shop owners, law firms, accounting firms, some of which started in South Bend and eventually moved to Chicago,” Grant says. At the community’s height, it supported six synagogues of various denominations.

Eventually, though, the community followed a scenario common to small towns all over the country. The neighborhood began to change, younger people moved away and Sons of Israel membership shrank. Originally started as an Orthodox synagogue, when membership declined, it switched briefly to Reconstructionist affiliation in the 1980s, but that didn’t work either.

“The Jewish community (in South Bend) was still thriving, but it went from having six synagogues down to having three really solid, vibrant synagogues,” Grant says. Sons of Israel, in the wrong neighborhood at the wrong time, wasn’t one of them.

By the turn of the millennium, the synagogue’s membership had dwindled, literally, to two: David Piser, president of the Michiana Jewish Historical Society, and his uncle, Mendel Piser. David was president and was responsible for the building’s upkeep; Mendel served as treasurer.

“We tried to keep the building together and do what we had to do for it not to fall apart,” Piser says. “There were four other congregations in town, and because of the competition, we weren’t getting enough members. The building was falling down and we couldn’t maintain it. Mendel and I ran out of funds.”

Grant puts it even more poignantly. “David was the last person to lock up the building,” she says. “He took the (Jewish) stars off the turret, locked the doors and walked away.”

The building then passed through a number of hands, first belonging to Indiana Landmarks, a non-profit organization whose role is to find new uses for old buildings, according to its director, Todd Zeiger.

“Our mission is saving historic places, beautiful places, and this is a really good example of that,” he says. The organization took over the synagogue building, stabilized it and oversaw a number of renovations, then sold it to the city of South Bend, which sold it to a private individual who was not able to perform more needed renovations. Eventually ownership reverted to Indiana Landmarks, which continued to seek a buyer.

There was a plan to turn the building into a museum, but that didn’t pan out.

“It would have been an incredible space if we had had unlimited resources, but in 2007-2008 the economy precluded it. It wasn’t possible for a smaller Jewish community,” Grant says.

Enter Andrew Berlin.

“The story really begins with me being involved with baseball,” he says. The CEO of a large firm, Berlin Packaging, the Chicago man says that around 2010 he started thinking about buying a Major League baseball team. He was already a part owner and investor in (and fan of) the Chicago White Sox along with Jerry Reinsdorf.

He expressed interest in buying the team, but “Mr. Reinsdorf wasn’t selling. He was having too much fun owning a Major League team,” he says.

The Cubs had just been sold to the Ricketts family, so Berlin was in a quandary.

“I didn’t want to have to travel too far to see my team play, and it was pretty slim pickings,” he says. “So I started looking at minor league baseball to satisfy my appetite.”

He lighted on the Silver Hawks. Their home was just an hour and 15 minutes from downtown Chicago and they are affiliated with the Arizona Diamondbacks. “That meant the quality of play was very high and you get to see future baseball stars,” Berlin says.

He bought the team on Nov. 11, 2011 at 11:11 a.m., a time that augured good luck, he believed. “Baseball superstitions play a big part in the game,” he says. “Apollo 11 was the first lunar module to land on the moon, and the day was Armistice (now Veterans) Day, so I thought the elevens would be good.”

That turned out to be true, with Berlin turning the struggling team’s fortunes around after hiring a new leadership team and sinking more than $12 million into renovations of Coveleski Stadium, the club’s home.

But first he had to make one more decision. The former Sons of Israel synagogue sat just outside the ballpark fence, directly adjacent to left field. It had been abandoned for years and Berlin could easily have torn it down and built a team store on the property. Or he could have let it sit where it was and built the store in a different part of the ballpark.

David Piser and a few others from the Jewish community had another idea, which they conveyed to Berlin. Why not renovate the building and use it for the team in some way?

“The idea didn’t appeal to me at first,” Berlin says, noting that a proper renovation would involve a new roof, new plumbing and more, and would cost at least $1 million. And turning the building into a team store, as some had suggested, didn’t make a lot of sense.

“Usually you want that behind home plate where the biggest crowds are. The left field fence is not the ideal placement,” he says.

Then he had second thoughts. “The building is beautiful, and the idea of bringing back the region’s first synagogue to its former glory appealed to me. Being Jewish myself, I have an affinity for beautiful synagogues. Today many synagogues are very modern, and that doesn’t really inspire me,” Berlin says. “If you’ve been to Rome, you can imagine G-d living in the Sistine Chapel, and I don’t get that from many synagogues today.”

He took a closer look at the building and found “the stained glass windows, the beautiful bimah, the chandelier were all extraordinary, but they were in disarray.”

Berlin first met with Jewish leaders in the community. “We ran our plans by them to make sure no one would feel slighted because we would be using the building for other than a place of worship.” There seemed to be few objections.

He also met with three rabbis, one from each of the major denominations. “There was no opposition,” he reports. “All three rabbis expressed that in the Talmud, any building that was used as a synagogue, when the use of that building ceases to be as a place of worship it ceases to be a synagogue. To use it as a team store was OK with them.”

The city transferred ownership of the building to Berlin and the undertaking began.

He sent the fragile, blackened chandelier – one of the former synagogue’s glories, originally believed to be used with candles – to a restoration and electrical company in LaPorte. Refurbishing it cost $40,000 – not a bad investment for a fixture whose estimated current value is around $200,000, Berlin says.

But he sees the chandelier in particular as more than a monetary investment.

“It is magnificent, and it has a metaphoric, symbolic value to the building,” he says. “It shines a light on everybody in the synagogue.”

Fittingly, it was David Piser who led the countdown to the light being switched on during the ceremonial opening of the team store in summer 2012.

But first much more work needed to be done. Workers built out the concourse fence enclosing the stadium to include the synagogue building, and the Star of David atop the building, the bimah and other aspects of the building were painstakingly restored, Berlin says. A phrase from Exodus about making a building a place of worship and sanctuary was painted on the front door.

“That’s to give our New Testament friends a little education on the Old Testament,” Berlin says with a chuckle.

He also commissioned a new version of a painting from the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel showing G-d stretching out his finger to touch Adam’s finger, giving him life.

In Berlin’s version, G-d’s hand holds a baseball glove and he is handing a baseball to Adam. Underneath it says “Play Ball.”

Another painting depicts Noah’s Ark, with the animals being loaded on and a storm coming. It’s titled “Rain Delay.”

With the paintings, Berlin says, “I’m just trying to have fun with my Old Testament roots. People know I’m Jewish, and the building is a huge highlight of the ballpark.” Visitors often have their pictures taken in front of the “Play Ball” painting, he says.

When the store is closed, members of the community can rent it out for parties and events.

Since he took the team over, Berlin says, attendance has more than doubled, the team’s finances are back in the black and the club made it to the minor league World Series. Merchandising figures are up more than 50 percent and the effort was named baseball renovation of the year. “The sports industry has taken notice,” Berlin says. In addition, a short documentary on the synagogue and its renovation won an Emmy Award.

Berlin doesn’t attribute all the good fortune to the synagogue, but he thinks it had something to do with the team’s “great karma.”

“We’ve done a lot of focus groups on the ballpark, about what people like and don’t like, and fans have told us that their number one favorite place in the whole ballpark is the synagogue,” he says. “There is a very small Jewish population here but a huge Catholic population. The synagogue has taken on a point of pride for the entire city.”

He marvels that, although the building was in what he calls a tough neighborhood, “it never suffered any vandalism whatsoever. The building commanded respect from everyone who saw it. Some folks think there might have been some divine intervention.”

Whether that’s the case or not, most members of South Bend’s Jewish community are pleased with the development, David Piser says, noting that, if nothing else, the building has now been listed on the federal and Indiana Register of Historic Places, meaning it can’t be torn down.

“Some people are very unhappy that it’s a team store, but at least it is saved from the wrecking ball and has been beautifully redone,” he says.

For himself, he believes “it’s a good thing. We’re going to have a plaque put up explaining that it was once a synagogue. It’s part of the history of South Bend and it’s been saved, and I’m happy with that. It’s not what we wanted, but it’s the best of all worlds.”

He would have preferred to see the building continue to be used as a synagogue, he says, but realizes that was impossible.

“That idea is gone, and it is what it is right now. Every time I drive by it I thank G-d for Mr. Berlin and his foresight to save it.”

His Uncle Mendel died in 2007, but he thinks fondly of him and his efforts when he sees the building, Piser says.

“Some people are aware that it’s a synagogue and some aren’t. When we get a plaque up, it will maintain the identity of a Jewish house of worship,” he says.

For Todd Zeiger of Indiana Landmarks, “it’s a great re-use for the building, and I’m glad we were able to play a role. Our role is to find new life for old buildings, and we like uses that respect the history of the building and its architecture and breathe new life in it.”

In the current instance, “it’s been done in a way that respects the space,” Zeiger says. “It’s all open inside. You still feel it used to be a place of worship. It’s a good marriage between its history and its new purpose as a team store, and it’s a real success in that regard.”

The local Jewish community “was thrilled,” according to Grant, the former Jewish Federation executive. “They were worried about vandalism (against the synagogue), and this seemed like the perfect shidduch. They did a beautiful job renovating it, including the historically significant chandelier.”

The building’s location is also significant, she contends. “It’s right in the middle of downtown, which is the place where the Jewish community lived and thrived for more than 100 years. Keeping it in the center of town was our goal. It was a bustling downtown, a whole melting pot right there, and revitalizing the whole area is exciting.”

The local Jewish Historical Society has the pews, Ark, Torahs and yahrzeit plaques, she explains, and are either storing them in their archives or giving them to other synagogues. Nothing has been lost.

“It’s a really special place, really unique,” she says. “Thousands of people are going into that space and they still enjoy it even though it’s not (being used for) the original purpose. It’s the best of both worlds.”

She says at the beginning of the process, some members of the community were unhappy with the idea because they were sorry it wasn’t going to remain a religious space. Those concerns, she says, have largely evaporated.

“Everybody knows it is the original synagogue in South Bend from 1901 and this will keep its memory alive a lot longer” than other options that were considered, she says. “I personally would rather see it repurposed like this than having a synagogue become a church and lose any flavor of what it was. This way, with the restored Jewish star on top, everybody who walks in knows exactly what it was.”

She suggests that as other small towns in Indiana and elsewhere face similar issues, they look to South Bend as an example of what is possible. “Communities all over Indiana and Illinois are looking at these issues, and you have to plan ahead,” she says.

But perhaps happiest of all is Berlin. “People love shopping there,” he says. “This synagogue has seen three different ballparks and has survived. There’s not a team in all of sports that has a synagogue there.”